Blog

Epistolary Imagery in Early Modern Paintings – Part I: Portraits

Occurring in European portraiture as early as the beginning of the sixteenth century, from the middle of the seventeenth century the letter became a very popular motif in Dutch painting. This can be partly attributed to the high degree of literacy in the Dutch Republic, especially in the province of Holland, which had the highest in Europe. Another factor was the increase in communication by letter due to the expansion and improvement of the postal system. The popularity of the letter theme reached its peak in 1660s and 70s, particularly in the form of the love-letter genre (see below and the forthcoming Part II of this blog). Dutch painters would provide the model for paintings of (mostly female) lovers writing and reading letters copied by painters all over Europe in the following two centuries. The letter was also a prominent attribute in trompe-l’oeil paintings, still-lifes of flat objects meant to deceive the viewer into thinking that the object is real (see the forthcoming Part III of this blog). For examples of all these three genres, see our (still growing) gallery of early modern paintings featuring letters.

Portraits

Letters for the first time appeared in paintings, if only occasionally, in portraits of men sitting at a table, in which they function as an attribute of learning. They represent the portrayed as a homo literatus, or man of letters, a well-educated and literate individual. Often they were portrayed at work, together with the tools of their trade: an ink pot, a quill pen, a knife to sharpen it, a stick of sealing wax – comparable to painters portraying themselves with palette and paintbrush.

Man Sharpening a Quill (1632), by Rembrandt van Rijn

More practically, letters showing an address were used to identify the person portrayed. At times it can be difficult to recognise a piece of paper figuring in the picture as a letter. Often it could just as well be a manuscript of another sort, or a newspaper, a music sheet, etc. In general letters can be recognised by a fold of paper in the hand of the portrayed or the folds in the paper showing when opened, or by a wax seal.

Portrait of an Elderly Gentleman in a Fur-Trimmed Coat (c.1575-1579), by Prospero Fontana

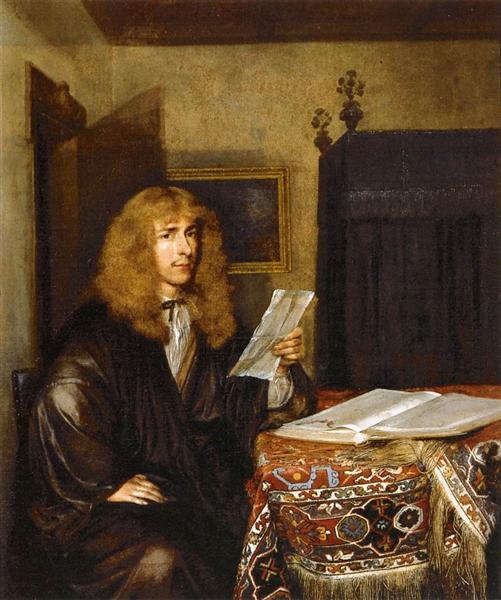

Sometimes it may be difficult to discern between a portrait, in which the person portrayed is meant to be identified, and a genre scene, which depicts fictitious people engaged in common activities and, when letters are concerned, commonly in a domestic setting, as in this portrait by Gerard ter Borch the Younger, who is best known for his genre paintings:

Portrait of a Man Reading (c.1675), by Gerard ter Borch

One would say that in portraits the person portrayed looks back at the viewer, whilst in genre paintings the characters are fully engaged in the activity that is depicted. However, this is a rule of thumb and there are also paintings which seem to deliberately play with the boundaries of the genre, for instance, in these portraits of the poet, diplomat, scholar and composer Constantijn Huygens, and of Dirck Wilre, Director-General of the Dutch Gold Coast (with letters lying on his desk):

Portrait of Constantijn Huygens and his Clerk (1627), by Thomas de Keyser

Dirck Wilre in Elmina (1669), by Pieter de Wit

Portraits of women with letters are rare, because they were not commonly associated with a life of letters. They were not supposed to write books and, as far as letter writing is concerned, given their domestic role should only write about private matters – whereas men corresponded about politics, religion, science, etc. Not even the learned Anna Maria van Schurman was portrayed holding a letter (see also the previous blog, about van Schurman). Portraits of women holding books, such as the Bible, the book of hours, or a songbook – expressing their religiosity or, in the case of profane songs, being part of a female education – were more common.

Portrait of a Woman with a Book of Music (c.1540-1545), by Francesco Bacchiacca

Women do figure on a large scale with letters in genre paintings, but these almost exclusively concern love letters, which can be inferred from amorous symbols embedded in the painting. Furthermore, women are seldom portrayed as writing letters. This may be related to the fact that women were primarily taught to read, but it was also custom to portray women in a passive pose, which reflected their dignity, humility and sobriety. Under the influence of the rising popularity of the epistolary novel in the eighteenth century, in which women acted as narrator, the number of portraits of women holding a pen (along with other writer’s implements) increased, which is a clear indication of changing views on femininity in which writing has become a feminine cultural practice.

Portrait of a Woman (formerly thought to be Madame Roland, c.1787), by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard

The next blog about epistolary imagery in early modern paintings will discuss genre and history paintings.

Further reading

- Svetlana Alpers, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1983, pp. 192-207.

- Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat, The Visible and the Invisible: On Seventeenth-Century Dutch Painting (transl. Margarethe Clausen), Berlin/Munich/Boston: De Gruyter, 2015, esp. pp. 219-257.

- Gerard Koot, ‘The Portrayal of Women in Dutch Art of the Dutch Golden Age: Courtship, Marriage and Old Age’, Images and Illustrated Essays on the History of the Dutch Republic, History Department, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, 2015.

You must be logged in to post a comment.