Blog

Utrecht Manuscript 985 – A Network Analysis

Manuscript 985 of Utrecht University Library is a collection of 43 letters by different authors, written roughly between 1560 and 1660, except for one letter which comes from 1756. One of the peculiarities of the letters in Ms 985 is that on first sight, they do not seem to have one common denominator. In this blog I will try to find out whether there is a rationale or logic that can explain the compilation of this manuscript.

Although they seem to constitute just a bunch of old letters, the letters in Ms 985 have at least one thing in common: the authors were all humanists. The letters were sent by or addressed to some of the most prominent seventeenth-century humanists of the Northern Low Countries, such as Arnoldus Buchelius, Lambertus and Adrianus van der Burch, and Caspar Barlaeus. The letters they sent to each other on a rather regular basis enabled them to keep in contact and to exchange their ideas. The letters connected them, and we could therefore say that these people formed some sort of network. With the help of analytical tools, such as Nodegoat, it is possible to analyse such a network using the metadata of the letters. This might bring us closer to finding the rationale of Ms 985.

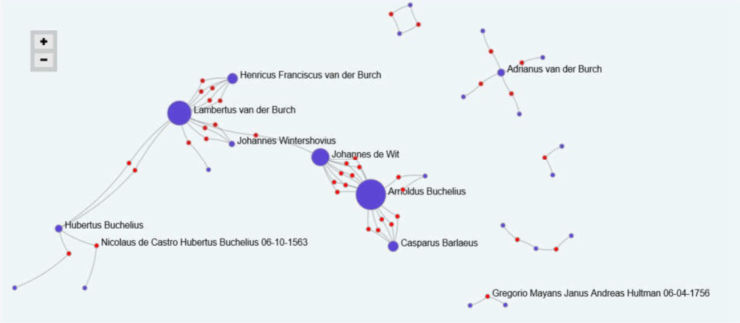

Figure 1 contains a visualization of the social network connecting the senders and recipients of the letters in Ms 985. The figure shows how Arnoldus Buchelius, Johannes de Wit, and Lambertus and Adrianus Buchelius were the most active and well-connected people of the network, as far as contained by Ms 985.

Figure 1: Social visualisation of the letters in MS 985; the blue dots are the authors and each line connecting them represents one letter.

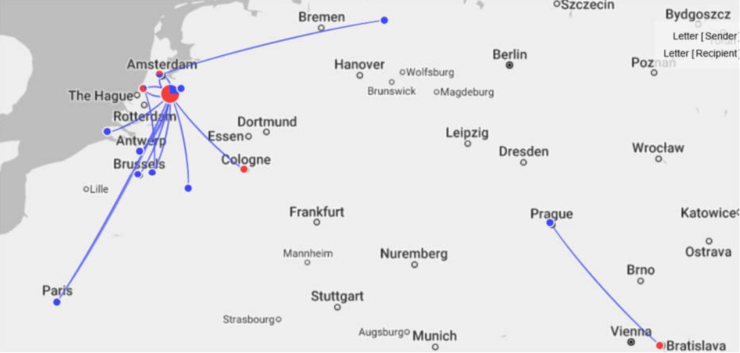

Based on the visualization in Figure 1, one is led to think that several of the people in the network were not in contact or did not know each other at all. However, we should keep in mind first of all, letters between seemingly disconnected people never found there way into Ms 985. But there is a second scenario: people could be very well connected without ever having sent a letter to each other, for example because they lived very close by. Therefore, scholars do not only want to know who sent a letter to whom, but also from and to which place the letter was sent. In the case of Ms 985, a geographical visualisation of the metadata results in the map in Figure 2. The map shows where the senders and recipients were at the moment of sending. In the case of Ms 985, one of them was often in Utrecht, which seems to take a central role in the network. In fact, many of the authors of Ms 985 lived in Utrecht and it might be possible that they knew each other without writing letters to each other. The geographical analysis therefore suggests that a connection to Utrecht was one of the criteria for the compilation of Ms 985.

Figure 2: Geographical visualisation of the letters in MS 985; each blue line connecting two places represents one letter.

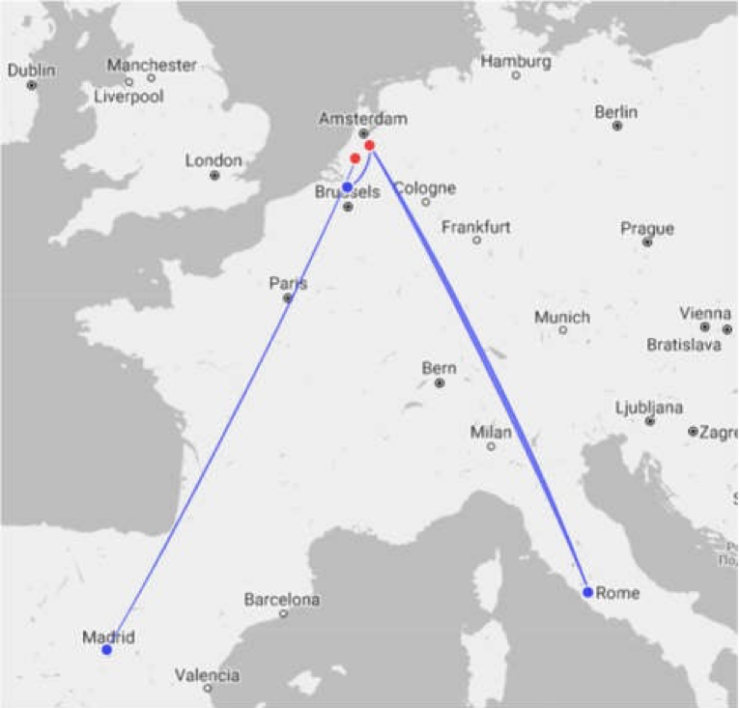

The University Library of Utrecht holds another manuscript that contains letters by many of the same authors who also feature in Ms 985. This manuscript is referred to as Ms 983 and it holds letters copied by the aforementioned Arnoldus Buchelius. This manuscript has been previously studied by another group of students. Buchelius copied out not only his own letters and those of the people in his network, but also letters he found elsewhere, that just seemed interesting to him. One example are letters written by the only Dutch pope in history, the Utrecht-born Adrian VI (1459-1523): see Figure 3. The majority of the letters in Ms 983 are from Buchelius and his friends, though.

Figure 3: Letters from Ms 983 sent between 1515 and 1522, including Adrian’s letters; each blue line connecting two places represents one letter.

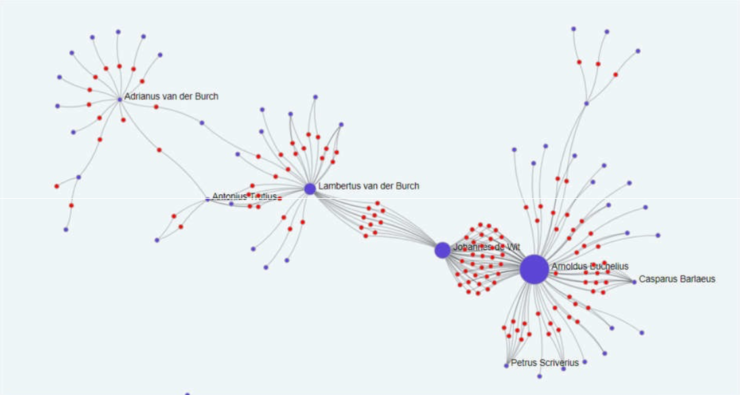

If we look at a visualization of the social network resulting from the letters of Ms 983, we are faced with a familiar picture. In the social network in Figure 4 the four most prominent persons are again Buchelius, De Wit and Lambertus and Adrianus van der Burch.

Figure 4: Social visualisation of the letters in Ms 983; the blue dots are the authors and each line connecting them

represents one letter.

Also the way in which the authors are connected is very similar to what we have seen in Figure 1. Because of the striking similarity between the two visualisations, one is led to think that the two manuscripts are connected in some way. And if so, Ms 983 may be able to reveal the rationale of Ms 985.

With the help of the metadata it is possible to see if there are connections between the letters in both manuscripts. This seems to be the case, because several letters in Ms 983 have exactly the same metadata as letters in Ms 985, which probably means that these letters are present in both manuscripts. Examples of such letters are the two sent by De Wit to Buchelius, one from Antonius Trutius to Adrianus van der Burch and one from Johannes Wintershovius to Lambertus van der Burch. A closer look at these letters reveals that practically all letters of which the original is present in Ms 985 lack a proper transcription in Ms 983; instead it contains only the metadata of these letters and refers to Ms 985 for their content. There is only one logical explanation why Buchelius did not copy a letter but referred to the original: he owned the original at the moment of copying. We know that Buchelius transcribed the letters in Ms 983 and thus he must have had access to the letters of Ms 985 as well. This corresponds with what we know of Buchelius, namely that he was a fervent collector of letters, which was a rather common practice among humanists. It is therefore very convincing that the rationale of Ms 985 is that they were collected by Buchelius. How the letters written after Buchelius’ death in 1641 ended up in the manuscript, remains still unknown. It might as well have been because of their similarity to the letters already in the manuscript or just because of mere coincidence, but this is something only future research could answer for sure.

Bibliography

Sandra Langereis, Geschiedenis als ambacht. Oudheidkunde in de Gouden Eeuw: Arnoldus Buchelius en Petrus Scriverius, Hilversum: Verloren, 2001.

Judith Pollmann, Een andere weg naar God. De reformatie van Arnoldus Buchelius (1565-1641), Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, 2000.

You must be logged in to post a comment.