News

Call for contributions: ‘How I got my Allen & Allen’

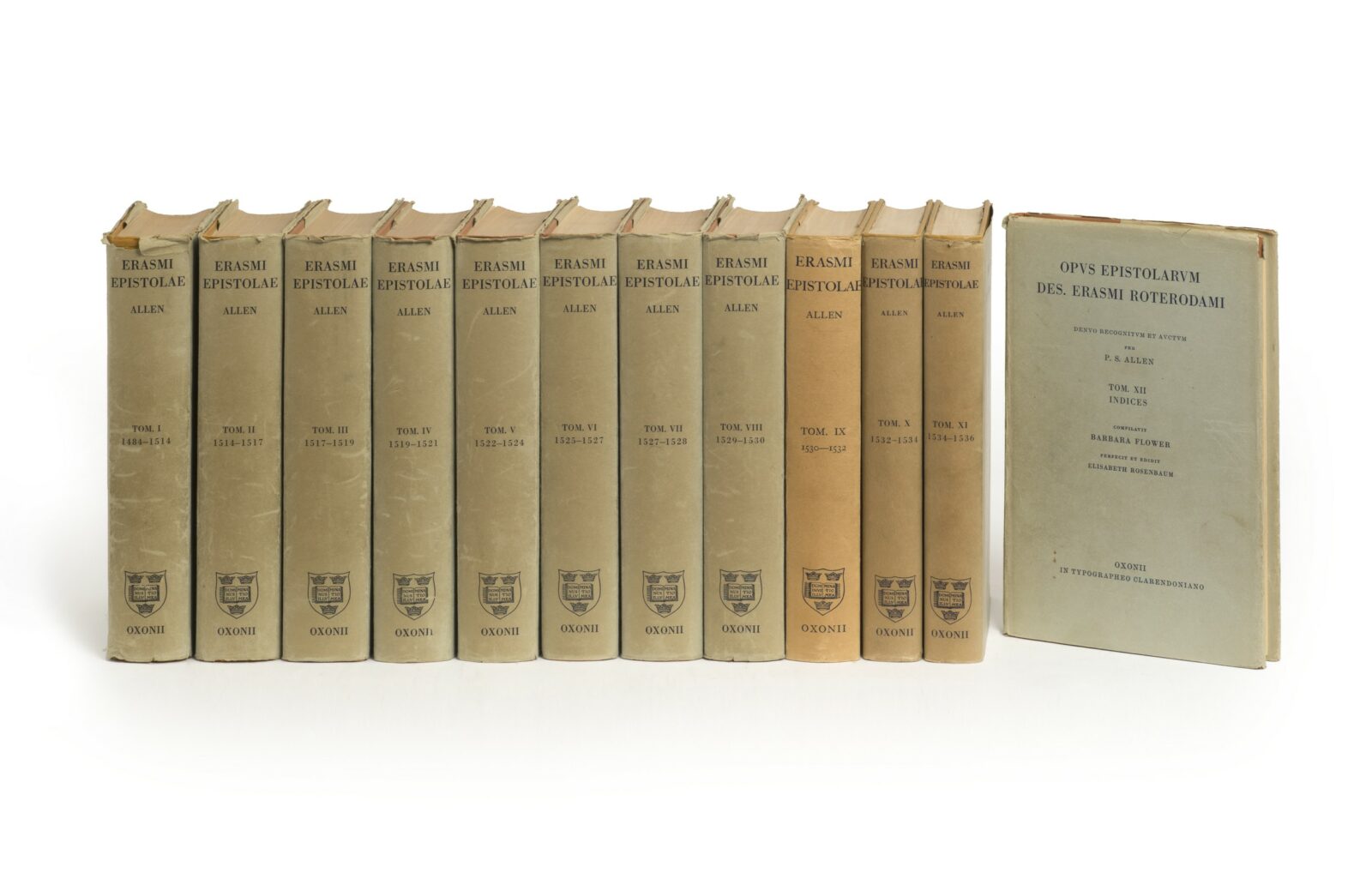

For a little side project, that has no particular reason or occasion, Dirk van Miert is collecting accounts of how scholars got their ‘Allen & Allen’, viz. P.S. and H.M. Allen’s edition of Desiderius Erasmus’ correspondence.

Over the years, he has noticed this is a particular table-talk theme at specialized conferences, and he thought it would be fun to collect these stories. Many of us got hold of a copy at an age in which ordering a brand new copy from OUP was no realistic option, financially speaking. So how did you did strike that bargain with a trusted local antiquarian? What former professor took pity upon you and parted with her second copy? Who had this sugar daddy who would place the order for you as a Christmas present?

An assemblage of these stories will tell us something about how students in the 20th century (or even the 21st century) negotiated the costs of scholarship, in particular in the pre-digital age. The expectation is that relations play a crucial role: master-apprentice relations, institutional relations, family, business-relations…

It is uncertain what will be done with the stories. Most contributions are expected to be rather short. If enough of them can be gathered to turn it into a booklet or an article of some sort, it would be a nice tribute to publish them (following all normal procedures, with proofs for all authors).

Below is Dirk’s story. What’s yours? Please send him your story (d.k.w.vanmiert@uu.nl), and if need be provide a title.

Allen & Allen: ‘Deselected’.

It was in one of my last years as a PhD candidate that I received a message from our Faculty library. To cope with the eternal problem of lack of shelving space, they were organizing their annual sale of books that were ‘deselected’ from the stacks. This time, it concerned books from the history section.

Our building held part of the open shelf collections of the humanities: the other collections were held at various other premises. One of these was the central university library, although it never became clear why some books were purchased twice, some only once, and why they ended up in the storage facilities of the central library or why on the shelves in our building or that of another department. There were further enigma’s. The acquisitions officers, at least in the past, never seemed to cooperate much: multiple copies of the same book were sometimes on the shelves of different departments. The language departments simply bought, or received, everything their staff produced, even if their staff produced historical stuff rather than studies relating to the history of literare. In many cases, the boundaries were artificial anyway, in particular when it came to early modern cultural history.

Duplicate copies were easy victims for librarians who got the order from above to weed out. During the ‘deselection’ process, the books were gathered in one room and before they started to sell them of to students for a euro per piece (or 2 euros if the book was particularly big or fat, or 50 cents if the book was rather slender), the ‘staff’ had the first choice. Staff was supposed to bid against one another – which no one ever did, because there was the silent understanding that the first bidder had the first rights. No one would seriously bid against a colleague in magnitudes of 2 euros. All that wasn’t sold to staff or students, would be transfered for something like 10 cents per kilo to second hand book traders, or even to traders in all sorts of paper.

As a PhD candidate, I had staff-rights, so the moment I read the email, I dropt everything and was one of the first to inspect the couple of square meters the librarians, in their laudable self-denial, had selected as burnt-offerings on the table of bureaucratic efficiency. I was particularly lucky with my personal interest: postclassical Latin texts. In the old days, when staff as a rule still read Latin, these were acquired by history and literature departments alike, these happily compartmentalised kingdoms. Thus, a modern edition of Bodin’s Latin translation of Six livres de la République could be found on the shelves of History, of French and of Neo-Latin (the latter a heir to the long-gone ‘Institution of Neolatin and Neophilology’, to which the stamps on the flyleafs still testified).

I used to bid the standard symbolical price of one euro on everything. I felt like a kid in a candy store. It was then that my eyes fell on twelve columns that looked like so many cilinders of jelly beans. The guilded letters on the light-brown spines sparkled in the cold tube lights. Twelve shields at the bottom were upheld by twelve white shelf-markers that covered what I new to read ‘OXFORD’. I still remember very clearly that at that point my personal excitement was trumped by a kind of moral exasperation: surely this book was not treated like the others? The idea that a second hand book trader would lay hands on a perfect looking complete set of Allen & Allen’s famous edition of Erasmus’ letters for a price of 50 cents, and that a University in a Capital City would be responsible for such an inflation, made me aware there was something morally wrong with all this. It was as if I heard Lucian laughing from up high that after 1800 years we were finally taking serious his satire on Philosophers going cheap. As a fully experienced politician in times of moral decline, I also had the immediate solution: it’s best that I bought them, before someone came along whom we did not know and did not trust. The copy was immaculate: evidently very few people had indeed been using it from the History shelves. The one on the Neo-Latin shelves looked much more worn, I knew (because I always used that one).

Hmm, how much to offer on this? Technically it was one book, but I thought I at least had to offer 12 euros – one for each volume.

And so I did. I do remember confessing to the librarian that it did not feel right that they dumped the most fantastic books. And I did have to wait until the end of the embargo, that is: the period that staff were allowed to make their choices and if need be bid against one another. But nobody put in a bid on Erasmus’ letters.

I myself worked at the department of Dutch at the time, but I remember that the professor of early modern history also harboured second thoughts when he heard that Erasmus’ letters had been sold for the price of a lunch. Until he heard it was purchased by me, he kindly added. Apparently, the misgivings I had voiced to the librarian had found their way up the command chain.

I graduated before the next sale. I don’t know if they ever changed the system – if anything, they must have stopped bothering about the few euros they might earn off their staff and must have proceeded to have the books pulped straight away, because only more books have been exiled to storage rooms (at best) or traders in old paper (at worst), since new departments moved in, whereas others moved to larger buildings with smaller library spaces.

But at least Allen’s edition is safe on my shelves ever since. The double stamp on the flyleafs indicate the old and new logos of the University Library. The shelf mark is still there: GES 35 L 8300.1-12, a sticker with bar-code crossed out with pen, and a new stamp: ‘AFGESCHREVEN. Universiteitsbibliotheek Amsterdam’. (‘RELEASED. University Library Amsterdam’). Curiously, now that I write this, my eyes falls on a pencil note on the flyleaf at the back of volume 1: ‘Coebergh f 270,- 12 delen, 31.8.71′. This suggests that the University Library itself purchased it 2nd hand for only 270 guilders, which means that they only paid 10% of the new price and paid this to Coebergh, once a large Catholic bookseller in Haarlem who catered to catholic universities and convents in Belgium and The Netherlands, taken over in 1982 it was taken over by Van Stockum. My sense of guilt quickly dissolves.

There was a time in which I thought certain books would only become more valuable in terms of money. That might not have happened with my Allen & Allen. But whatever I paid for it is irrelevant: as a set, it is one of the prize-books in my own small library, and I hope to make sure that it will pas silently into the hands of a young scholar again, once I myself find no use for it any longer. I am pretty sure this edition will outlive myself.

You must be logged in to post a comment.